TURIN, Italy – Diego Nargiso, the 1987 Wimbledon junior champion with outstanding technical and athletic skills, is the symbol of the unfulfilled talent of an Italian tennis era that was adrift before the “Renaissance” now embodied by Jannik Sinner.

If he were born today, what would that brilliant left-hander, a serve-and-volley player who reached No. 67 in singles and won five doubles titles, peaking at No. 25, find?

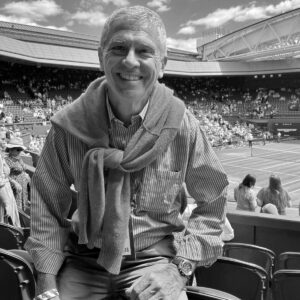

“He would find a different atmosphere and a world No. 1 who dominates and therefore takes the spotlight. That would allow him to grow more calmly,” said Nargiso, now 55, in an interview with CLAY in Turin, during the ATP Finals (formerly known as the Masters).

“He would find important points of reference, which today are represented by a strong federal team structure, to grow both as a person and as a player. He would find significant examples, highly qualified, for a boy who has a clearly defined path,” Nargiso explained.

Italian tennis has always produced talent, but many of those players were lost along the way, often upon turning professional. They all lacked something: some the physique, others the technique, and others the mental strength. Today, Italian coaches are the key behind the boom.

The left-hander belonged to a transitional generation that neither shone with the brilliance of Adriano Panatta and his peers in the 1970s nor broke records like Sinner does today, supported by Lorenzo Musetti and Matteo Berrettini.

Nargiso was part of the group led by Andrea Gaudenzi, now the ATP Chairman, which also included Renzo Furlan, Omar Camporese, Cristiano Caratti and Paolo Cane.

“Back in my days, there wasn’t much of a plan or common purpose — there was no shared project, and strength multiplies when the vectors align and move in the same direction. That way, you never completely fail: without conflicting interests, growth becomes collective and consistent,” he acknowledged.

Interview with Diego Nargiso

– Why did this happen?

– My generation are the sons of Adriano Panatta, Paolo Bertolucci, Corrado Barazzutti and Tonino Zugarelli — the four from Italy’s 1976 Davis Cup team. Great players and also great coaches. Personally, their knowledge gave me a lot technically, but when in 1990 the new ATP ranking system was introduced, it completely changed the rules, forcing players to compete more often and therefore to focus more on the physical aspect and less on technical details. Perhaps my mentors didn’t have the curiosity to find out what was needed for players to make that next qualitative leap. Tennis changed from the 1980s onward. We also trained six or seven hours a day, but in a disconnected way. At 18, I was already working on the mental side, and Professor Umberto Longoni travelled with me to Wimbledon and Paris. But there wasn’t an integrated system of training and player support. The organisational side and coordination between different departments were missing. In fact, there were strong defenders of the Davis Cup and strong detractors. And a divided environment doesn’t help those who need to grow.

– And what happened then to you and to that other unfulfilled talent, Omar Camporese?

– We grew up disoriented; we had to learn the hard way, little by little, over time — and that’s why we got lost. Because an athlete needs absolute confidence in himself, which is built through the continuity of work and through knowledge that’s constantly developed, both from direct and indirect experience. But the guidance we received could be misleading: a negative experience, a defeat, was considered a failure, when in fact we should have seen it as a learning opportunity. Then there was that structural and organisational mistake — abandoning the 18-year-old once he was no longer a junior and had to make the leap to professionalism, managing himself after being completely guided by the Federation. Some succeeded, and did it well — like Renzo Furlan and Cristiano Caratti — but they had the same mentor in Riccardo Piatti, who had worked with them since they were 14 at the national training centre and continued with them at Le Pleiadi in Moncalieri.

– What mistakes did you make, and how would you define your tennis career?

– I feel I achieved less than I could have. However, a player’s career also depends on how much he invests in his work on a daily basis. I was probably too immature to be a professional and didn’t take advantage of the lessons and advice given to me for my own good. Everyone was pulling me in different directions… Gunther Bosch signed me at 17, declaring I was Boris Becker’s heir. And (Nick) Bollettieri did the same. Both suggested that I shouldn’t play Davis Cup until I had matured physically, because I needed to take two months a year to prepare for clay, which disrupted my schedule, as I was more focused on faster surfaces. But I looked up to the captain, Adriano Panatta, and to my passion for the national team.

– What are the secrets of this Renaissance that you wish you’d had at 18?

– First of all, the Higher Institute of Training that Michelangelo dell’Edera has developed and directed over the years, which is extraordinary. There are not only more coaches who play and teach tennis, but they are also well-educated, modern, up to date, and capable of supporting young players with proper knowledge and understanding. They are teachers but also educators — all within an organised system that keeps growing thanks to knowledge exchange with professionals abroad. This is the Italian system that other countries are trying to imitate: plenty of study, constant interaction online, forums and workshops with top international coaches. This way, you stay informed, you share ideas, and you keep growing. Another very important factor has been SuperTennisTV, born from a great idea by FITP president Angelo Binaghi, which brought our sport into fans’ homes, with huge educational and promotional impact. And then the former players, almost all of whom became coaches, were crucial too. Myself, Furlan, Vincenzo Santo, Stefano Pescosolido… we met in Tirrenia to exchange experiences, which we then multiplied in the hope of achieving better results with the next generation. Who better to understand it than those who have lived it?

– And now, and tomorrow? After the boom of 1976, Italian tennis fell into a kind of slumber, and after the success of the Fed Cup team, there wasn’t a long-lasting wave, despite Schiavone’s and Pennetta’s Slam titles.

– As Binaghi said, we’re now working for the time when Sinner will no longer be there — ten years in advance — because we hope he’ll stay for a long time. But when difficult times come, the federation will have the duty to develop many high-level players. Like France, which still hasn’t found another Noah. If the system keeps pushing in the same direction, organised and willing to help itself, we won’t let the next champion slip away again.

If you enjoyed this interview with former Italian player Diego Nargiso, you can read many more conversations with the great stars of the circuit on our website.