PARIS – “Serbia!”.

When it was all over, when Novak Djokovic had already praised Casper Ruud, thanked Amelie Mauresmo, sweetened Yannick Noah’s ears and talked about his family, his team and left advice for the youngsters to build their own path, the world number one went back to the source of it all, to the basis of his titanium mentality, to the reason he is always ready for one more effort and has won, this Sunday in Paris, his 23rd Grand Slam title. More than any other man in tennis history.

“Serbia!”.

It is often said that tennis is just tennis and sport is just sport, but it is not always so. It can’t always be so. In pursuit of his 23rd Grand Slam title, which would make him the most successful tennis player in history, Novak Djokovic is driven by an inner fire that goes far beyond sport, rooted in his personal history and that of his country, Serbia.

Djokovic’s sporting success would be impossible to understand without taking into account his feelings for Serbia.

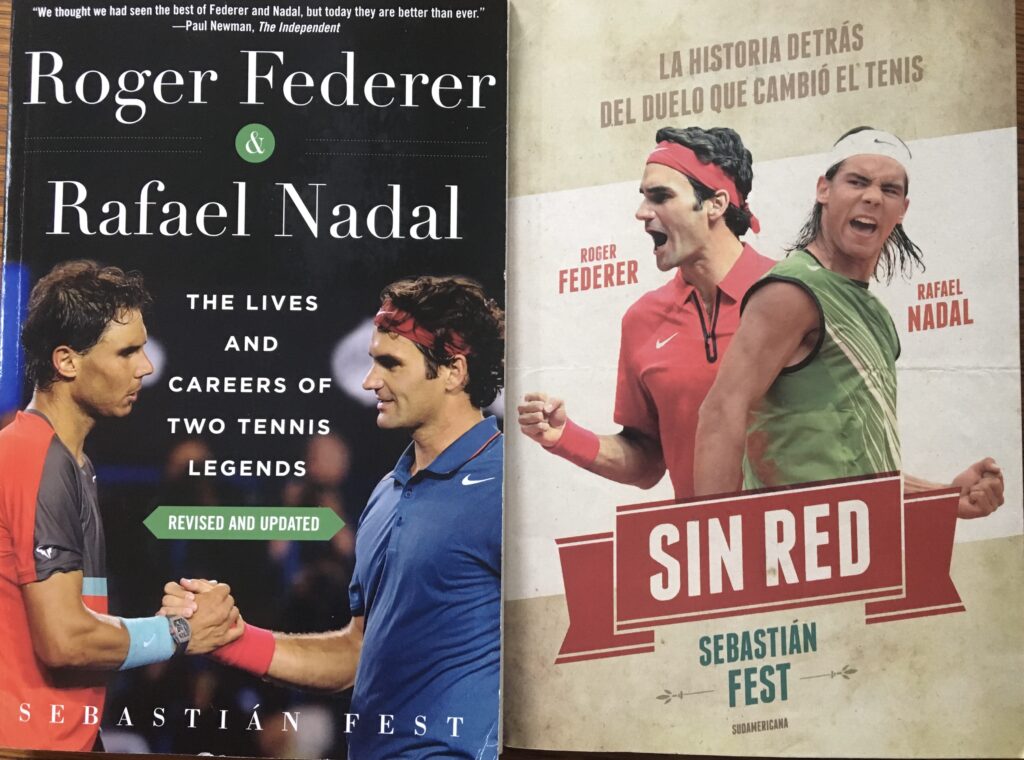

After the success in Paris, it makes sense to revisit scenes and conversations with the Serb that were part of “Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal: the lives and careers of two tennis legends”, a book in which the focus is on the rivalry between Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, but in which Djokovic has a very important share of the limelight.

**********

April 2012. Djokovic is comfortably seated on a brown leather sofa at the Monte Carlo Country Club and ready to answer my questions. And there is one question that has been on my mind especially after years of watching him, even since 2007 when he first shone on a big stage winning Miami: nobody would say that Djokovic is not a nice guy, quite the contrary. Another thing is that many believe he is spontaneous, while others feel that even his spontaneity is calculated. What is clear is that Djokovic always seeks to please, he has a need to please. He wants, indeed, to be liked. Ardently. He admitted it himself in that conversation on Prince Albert’s land.

– Is there some extra pressure, a need to be even nicer and more likable than average because he comes from Serbia?

The question caused Djokovic to settle back on the Monegasque couch, more motivated than nervous about the question.

“To be honest, it’s a good question, because I remember when I was travelling with my father playing junior tournaments all over the world. Most of the time, when we said we were from Serbia, people became very cautious and cautious about following us.”

The memory hurts Djokovic, you can see in his gesture that it made him suffer.

“The feeling was very ugly. First of all, because I don’t think anyone should be prejudiced about people, whether it’s because of where they come from or their religion. But I also understood it, because most of the international press had been writing negatively about Serbia. It started like that, but over time people came to appreciate me and my family, to understand that what we do we do with a clear heart and conscience. People respected me for my success, and that was important, to allow people to see my true personality and that the Serbian people are good and can be good.

The war in the former Yugoslavia is a very serious issue for Djokovic and his family. Around him, stories are interwoven which, like those of any war, are not pleasant. The best known is those nights as a child in his aunt’s bomb shelter, but there are many more.

A “New Yorker” journalist asked him years ago, in an extensive profile, if he agreed with the public apology made by the then Serbian president, Tomislav Nikolic, for the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, in which Serbian troops killed 8,000 Muslims.

“Let’s not talk about that, please. I don’t want to go into it, because anything I say can be understood in a very bad way. All I can say is that war is the worst thing a human being can experience.

Faced with less specific questions, however, Djokovic has no problem elaborating.

“It took me a while to understand, when I was younger, how serious the situation was in our country, especially after the war. In ’99 I was 12 years old, and in ’92 I was five. There have been many political and economic problems in Serbia in the last ten years. Standards are very low and people suffer. As in any country in the world, but especially there, because it is a country marked by war. The experience of overcoming that suffering brought me closer to my people and made me appreciate the true values of life. It made me, in a way, motivated to represent my country in the best possible way and to use the opportunity to show that Serbia has many positive aspects, not only negative ones.

“It’s a process, it can’t be just me influencing the image, there has to be more people. As a sportsman I do everything I can to win matches, and if I have the time and the opportunity, to represent my country in the Davis Cup, which is also a way to talk about the positive values that Serbia has. What I have been seeing in the media about Serbia in the last 20 years is very bad. The focus of the media every time they talk about Serbia is the negative. The violence, the criminality, all that. And that is something I definitely oppose and I want to change.

Four years before that interview in Monaco, Djokovic had been confronted with politics in the face of a direct question: What do you think about Kosovo’s independence?

It was 2008, Djokovic was in Dubai, the conversation was taking place in a huge garden at the “Aviation Club” in the emirate city. A few metres away, an artificial lake and palm trees protected from the sun. Djokovic, who three weeks earlier had won his first Grand Slam title in Australia, did not hesitate to respond: “They take away everything we have. Kosovo is Serbia and it will remain Serbia.”

“Kosovo is the heart of the country; can you imagine a country where a majority say they want to be independent and they do it? How would they feel? They take away something that is our history, our religion, everything we have.”

The then world number three’s face hardened when asked if he put himself in the Kosovars’ shoes, if he is able to understand their reasons, the desire to cut ties with Serbia after a war that shook the conscience of Europe.

“I don’t want to think along those lines. I know the history, there is a lot of talk about it. But, as I said, it was Serbia and it will remain Serbia, always. My father was born there, my uncle was born there, most of my family lived for 30 years there. I was there visiting many times the churches. You cannot imagine how many churches, monuments and historical sites there are there. I can’t think of Kosovo being another country”.

“I, as a professional, know that I have to keep playing and winning. I never knew much about politics, but this is not just politics, it’s really serious.”

Fifteen years after that conversation in Dubai, Djokovic’s sentiment didn’t budge an inch.

After his first-round victory, Djokovic wrote on the TV lens: “Kosovo is the heart of Serbia. Stop the violence”. He did so by including the symbol of a heart, rather than the word, in response to the violent clashes in Kosovo, where dozens of NATO peacekeepers were injured.

Two weeks after that public and internationally high-profile demonstration, Djokovic won what is one of the most important matches of his life. Much more than tennis, much more than sport.