MADRID – ‘But who are these guys sitting on the bench now?’ Manel Serras, one of the best tennis journalists Spain has ever had, began a column in February 2000 with these words, just after the Spanish team defeated Italy 4-1 in the first round of the Davis Cup. The phrase is not Serras’s own: the author explains that it was the general feeling at the Murcia Tennis Club that weekend. Something strange had happened, yes, and surely many fans did not know at first who the man occupying the captain’s chair was. Many would probably have expected it to be the legendary Manolo Santana.

Back then, it wasn’t as simple as taking your phone out of your pocket and typing the magic words ‘who is the Spanish Davis Cup captain’ into Google. If they had been able to do so, the most clueless fans would have discovered that the man at the helm of Spain was Javier Duarte, known as Dudu. But the surprise would have been even greater if they had dug a little deeper: because Dudu was only one of four captains Spain had. Yes, you read that right. Not one, not two, not three: Spain had four captains that season. The project, dubbed G-4, was one of those strange gambles that occasionally occur in sport and turn out to be winners. Because in 2000, Spain ended up winning its first Davis Cup title.

But to understand the success of the final against Australia in Barcelona, which is now 25 years old, we have to rewind more than a year. We are talking about the autumn of 1999 in Spain, a country radically different from today and which, in sporting terms, was going through a strange period. Five-time Tour de France champion Miguel Indurain had retired a couple of years earlier, the football team was still immersed in its curse of falling in the quarter-finals, and the successes of the Barcelona Olympics were now a distant memory. No one knew it then, but the most successful decade in the country’s history was about to begin, with the generation of Rafael Nadal, Pau Gasol, Fernando Alonso, Andrés Iniesta and company.

But in the autumn of 1999, no one could have imagined that Spain would become a world power in sport. It was under these circumstances that a very unusual pact was sealed that would ultimately lead Spain to win its first Davis Cup. Because yes, everything that happened in December 2000 at the Palau Sant Jordi in Barcelona in the final against Australia was a direct consequence of that revolutionary and groundbreaking agreement.

And who knows what would have happened in Spanish tennis, what would have happened to Rafael Nadal, without that victory that laid the foundations for Spain to lift five more Davis Cups in the 21st century, more than any other country. The story could have been very different. Spain had reached two Davis Cup finals, in 1965 and 1967, with Manolo Santana as the leader on the court.

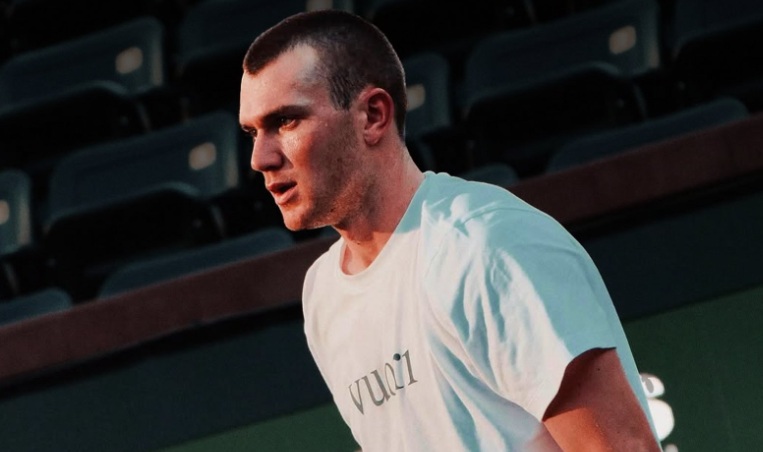

And it was Santana who was the Spanish captain in that distant 1999, when everything came to a head. Spain had some very good players: Álex Corretja, Carlos Moyà, Félix Mantilla, Albert Costa and Pato Clavet were all in the top 30, and a very young Juan Carlos Ferrero, future world number one and current coach of Carlos Alcaraz, was rising through the ranks at a dizzying pace. However, Spain was still unable to get close to the Davis Cup title. In 1999, in fact, it lost in the first round at home to Gustavo Kuerten’s Brazil and had to play a play-off against New Zealand to save its place in the competition.

‘We had had a good team for quite a few years but were unable to take that final step. The captain was Manolo, who had tremendous prestige, so it was a delicate situation for everyone,’ recalls Javier Duarte, who was Corretja’s coach at the time, in a conversation with CLAY and RG Media. “In 1999, shortly before the Palermo tournament, we had a meeting attended by quite a few players and coaches. We had already discussed it before, but of course, who were we to change the coach? We couldn’t do that.”

What those present thought at the time – not everyone was there, and those who weren’t weren’t informed – was to offer the Spanish Federation a shared captaincy: instead of having a captain appointed by the organisation, the players’ own coaches would be in charge of calling up players and selecting the teams for each round. Duarte coached Corretja, Jordi Vilaró guided Mantilla, Francisco Clavet was under the orders of his brother José Manuel, and both Moyà and Costa shared Josep Perlas as their coach.

The players and coaches gathered together and gave the idea the green light. ‘Why don’t we go to the Federation and propose it to them?’ they asked themselves. The plan had two very positive aspects. On the one hand, it would be much cheaper for the Federation because it would not have to pay for the technical team’s travel to tournaments: that was already financed by the players themselves, who were responsible for paying their coaches’ salaries and travel expenses on the ATP circuit. And on the other hand, who would know better how each player was doing than their own coach?

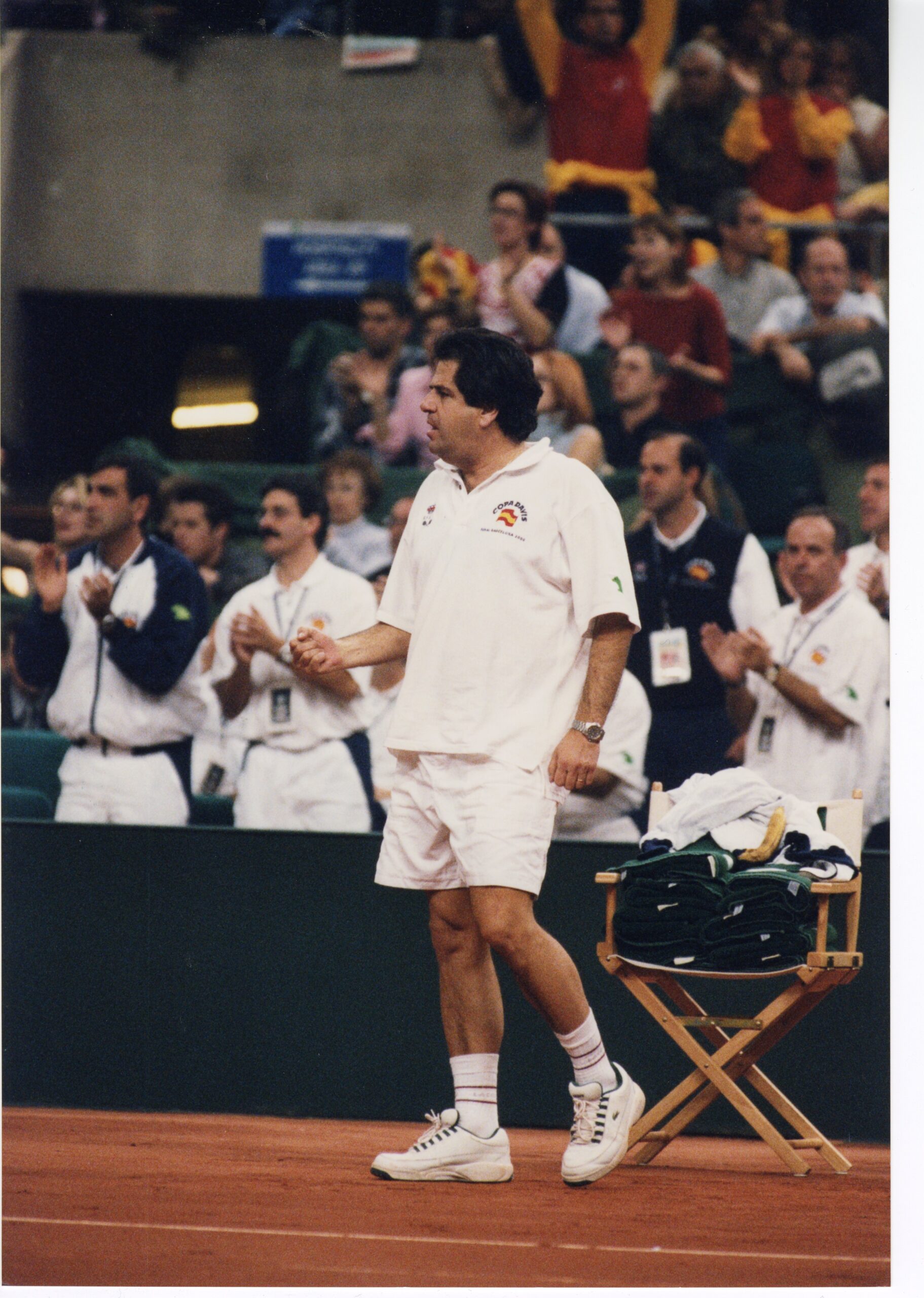

However, the proposal had several issues that made their hair stand on end. The first of these was called Manolo Santana. With Nadal still a child, Santana was then the absolute legend of Spanish tennis. A pioneer, charismatic and with great people skills, the Madrid native was enjoying his second spell on the Spanish bench, and who would dare to remove him from his seat?

The second problem was how to approach the federation, because shared captaincy was something that had never been seen before. After Santana’s Spain beat New Zealand 5-0 away in the 1999 play-offs, those involved arranged a meeting with the president of the Spanish Federation, Agustí Pujol. “At first, he wasn’t very enthusiastic. We were presenting him with a big problem: firing Manolo and bringing in three captains. In fact, we had to explain it to him twice so that he would understand it properly,‘ Dudu now recalls. ’But he was very brave. Agustí called Manolo the next day and dismissed him.”

The agreement that was finally signed was for four captains: Duarte, Vilaró and Perlas as coaches of the players and Juan Avendaño as the strong man of the Federation. The latter was a sine qua non condition set by Pujol in order to get the approval of the Board. The G4 was born.

‘It helped to create a more united team. In the end, the coaches lived with the players and knew all the details, who was better, who was worse. And it also guaranteed their commitment to play in the playoffs,’ says Francisco Clavet 25 years later in a conversation with CLAY. Neither he nor his brother Josè Manuel, his coach, knew anything about the meeting where everything was decided. But neither did they feel left out: Francisco played in the first play-off against Italy in 2000 and was in the stands during the final in Barcelona.

“The draw for 2000 had been very good and all the play-offs were going to be in Spain until the hypothetical final. There was a great opportunity because there were good players, and they understood that it was time to do something new. I think they would have won anyway, but it is undeniable that having four captains helped to put egos aside and smooth over certain moments in which, with a single captain, the tension would have skyrocketed,” adds Francisco Clavet, winner of eight ATP titles and ranked 18th in the world.

There were two such ‘moments,’ and Duarte remembers them very well: when Carlos Moyà was told he was not on the list for the final and when Álex Corretja was told he would not be playing either of the two singles matches on the opening day despite being the team’s number one player. It should be remembered that both Moyà’s coach (Perlas) and Corretja’s coach (Duarte) were two of the four captains.

‘They were two very difficult decisions,’ admits Duarte. “And for me, personally, Corretja’s was very hard because of everything that united us. We had been together since we were 11 years old, we were in the Davis Cup final in Spain, he was the leader and I was one of the captains. With all that, I had to tell him he wasn’t going to play on the first day. He cried like a baby, he was furious, but he understood my reasoning.”

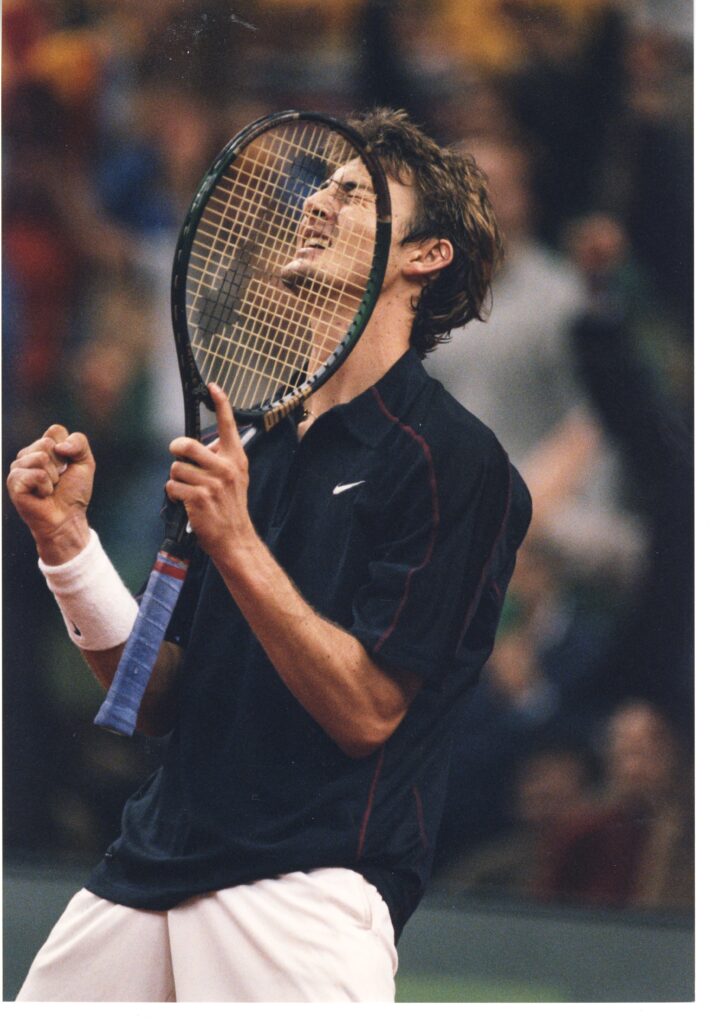

The idea was for Corretja to play doubles with Joan Balcells on Saturday and be fresh for a hypothetical fifth point on Sunday. But it wasn’t necessary: Lleyton Hewitt defeated Costa in the opening match, Ferrero tied the score against Patrick Rafter, Spain won the doubles, and on Sunday, December 10th 2000, in the fourth point, Ferrero sealed the final victory against Hewitt. Spain had made history, winning its first Davis Cup. And it had done so with four captains.

Beyond the honours, the victory of that G-4 was a triumph of bold management and collective vision over individual ego. The traumatic dismissal of a legend like Santana, the courageous yes from Agustí Pujol and the painful sacrifice of Álex Corretja and Carlos Moyà laid the foundations. That first success, revolutionary in its conception, was not an isolated coincidence, but the seed of today’s power. Who knows what would have happened in Spanish tennis without that triumph which, with four brains at the helm, opened the floodgates for Spain to lift five more Ensaladeras in the 21st century. Without that quartet, history could have been very different.