SÃO PAULO – The excitement surrounding Brazilian tennis today is greater than that generated by Gustavo ‘Guga’ Kuerten a quarter of a century ago. There has never been a better moment, says Fernando Meligeni, a sound player in the 1990s known for his passion and boundless dedication, who is now also a sharp commentator on the sport.

‘This is a very important moment for Brazilian tennis, one that we didn’t even experience in Guga’s era,’ said Meligeni, 54, during an interview with CLAY in São Paulo. ‘All the companies are killing themselves to get into tennis,’ he added.

In those years when Kuerten changed the history of Brazilian tennis with his three Roland Garros titles and his conquest of the world number one ranking, Meligeni was also there.

A semi-finalist at Roland Garros in 1999, the year he reached number 25 in the world rankings, the Argentine-born Brazilian is a powerful voice in his country’s tennis as the leader of a podcast with a growing audience, New Balls Please, which he shares with journalist Fernando Nardini.

The interview with Meligeni in Sao Paulo, the largest city in the West, took place days after the great success of the WTA 250 held there, which adds to the ATP 500 in Rio de Janeiro.

Brazil hosts the biggest tennis tournaments in South America, in keeping with its status as the world’s ninth largest economy, although Meligeni – and he is not alone – repeatedly and admiringly highlights the tennis powerhouse of a neighbouring country that continues to produce players: Argentina.

This is the first part of the interview with Meligeni; the second part will be published in the coming days.

– How would you describe this moment in Brazilian tennis?

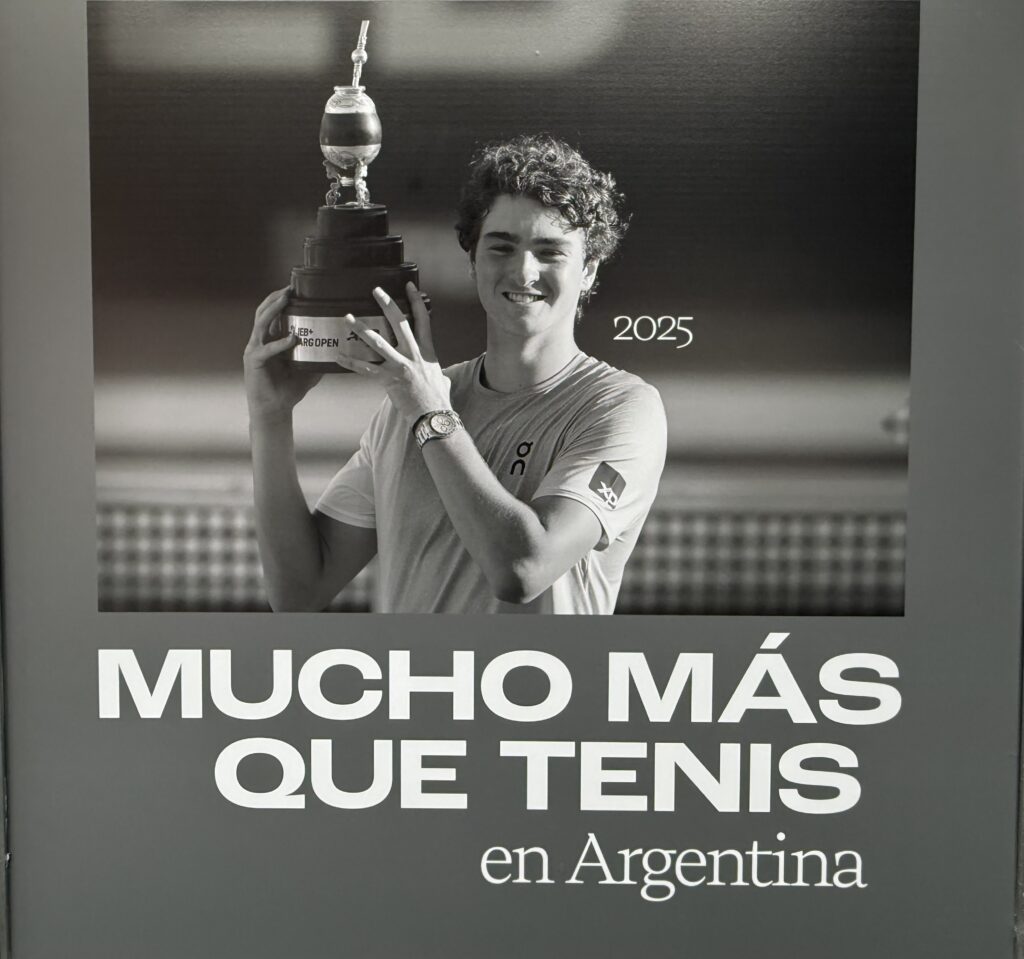

– The strength of Argentine tennis is still unmatched, incomparable. But Brazilian tennis is coming on strong. We have Joao (Fonseca) and Bia (Beatriz Haddad Maia) as the two big names. They have their good moments and their bad moments, but you have two players in the top 50 in the world rankings and with a strong presence in Brazil. And there are other young players coming up behind them. So people are starting to discover tennis and dispel the big problem that Brazil has always had, the idea that tennis is an elitist sport. The idea that it’s nice, yes, but very expensive.

– Is it?

– That’s always my big fight with people. I ask them, do you like tennis or not? It doesn’t matter if it’s elitist or not, if it’s popular or not.

– That’s the big difference with Argentina, isn’t it? Starting with Guillermo Vilas in the 1970s, tennis was adopted by the middle classes.

– Of course, that’s why I say, do you like it or not? What’s the problem if you like it, what’s the problem? No one can tell you that you can’t like tennis.

– I understand that the hype generated by Fonseca, which reaches all audiences, contributes to changing that perception.

– My 15-year-old son, who, despite being the son of a tennis player, has never watched tennis in his life because he doesn’t like sitting in front of the television, says to me, ‘Dad, is Joao playing? But you didn’t even like watching me play! Do you like watching Joao? And yes, he does. But at the same time, there’s another factor, which is the sponsors. All the banks are in tennis today. All the insurance companies are in tennis today. Many are fighting to get into tennis, and that fight is great for the sport.

– A moment greater than that generated during the Kuerten boom, I understand.

– Yes, it’s a very important moment for Brazilian tennis that we didn’t have even in Guga’s era. At that time, Guga had 25 sponsors and I had one, but they were sponsors of the player, not so much of tennis.

– And Brazil wasn’t that economically powerful yet…

– Of course. Today there are seven sponsors and 20 waiting.

– Another change in Brazilian tennis is how well organised the two main tournaments are, the ATP 500 in Rio de Janeiro and the WTA 250 in Sao Paulo.

– Very nice tournaments, they are always full. The public buys all the tickets in two minutes, which is a bit like what happens in Argentina. No matter how the country is doing, no matter if there is money or no money, people want to go to tennis. Why? Because tennis is growing today.

– Are you seeing children or teenagers choosing tennis instead of football, basketball or golf? Is that happening?

– Yes. Today we are entering the battle of what sport you are going to play, although we are still far from being the sport we would like to be.

– Djokovic was certainly kind in his response to the journalist, but the fact that he watched Joao Fonseca during the Davis Cup in Athens and said he wouldn’t rule out coaching him one day contributes to the atmosphere of excitement, doesn’t it?

– Of course, people get excited and say, ‘What if this could happen?’ Everyone has their own quirks. Some people stop playing and don’t even want to watch tennis, while others stop and want to keep travelling. I stopped because I didn’t want to travel. If you put Alcaraz in front of me saying, “I love you, Fer,” I’d say, “Give me a kiss then, because I’m not going to travel with you.” And it’s not arrogance, it’s just that I don’t see myself travelling 30 weeks a year, 20 weeks a year.

– But once you left tennis as a professional player, did you continue playing?

– Yes.

– Because many retire and don’t want to touch a racket…

– I never stopped. I never stopped watching tennis, I never stopped working in tennis. Everything I have has to do with tennis. I don’t have anything else. I don’t have restaurants. I don’t have money in the stock market. Everything I do and earn money from or in the media has to do with my books, my podcast, an online tennis course, tennis clinics, or events where I’m a speaker. And I’m an ambassador for tennis brands. Everything I am is tennis.

– When you see Fonseca, do you see something really great or is he putting too much pressure on himself?

– I believe very much in who you are and not what you can be. I’ve seen a lot in my tennis life. Who’s going to be number one, who’s going to be a top player, who’s going to win a Grand Slam. That’s fine. I’m also going to buy a helicopter and have 20 children. But no, that’s not how it works. Fonseca is a phenomenal player; I think he’s very good. We’ve never had a player of that calibre, not even “Guga” as a junior, at 18 or 19, played the tennis that Joao plays. That’s undeniable. And that’s incredible. Joao has a very good head on his shoulders, he can handle the pressure very well, he has a very good family and he’s doing everything right. Even the pace they’re setting for him is, in my view, the right one, because physically he’s not yet at the level of Alcaraz and Sinner. Putting him out to play every week is a mistake, but there’s a lot of pressure to put him out every week. I see it with the podcast. When Joao plays and plays well, I have 30, 40, 50,000 listeners in a week. When he doesn’t play, it’s 20, 18, 15, 17,000.

– So you recommend calm with Fonseca.

– There are so many people who played really well and didn’t make it… Look at the case of Bia Haddad, everything that’s happening to her. Imagine if she hadn’t already made it to the top ten! She’s at a very difficult point in her career, she’s hesitating. Everyone is trying to help her, everyone is talking. You see her go up 4-0 in the third set and then lose. Why? I don’t know. So, I think it’s unfair to predict how far Joao will go, given the difficulties of the circuit. He’s not in the top ten today, he’s in the top 40. Look, the difference between Argentina and Brazil is very interesting. The Argentine sings in the stands, he doesn’t seem to think, but he respects the guy who’s playing. Argentinians know that Messi is Messi, De Paul is De Paul and Juancito is Juancito. But they cheer for Juancito and sing. In Brazil, we don’t sing as much, but we believe that Juancito is Messi, that he is Neymar. We go crazy when athletes appear, because there is a great lack of idols in Brazil, a great lack of idols.

– Outside of football?

– In everything, we don’t have any in football either. The biggest idol isn’t treated like Messi, there are a lot of people who love him and a lot of people who don’t like Neymar. So who is Brazil’s biggest idol? Senna.

– Yes, but he’s no longer alive…

– “Guga” was, and now he’s a bit more retired. In volleyball we have big names, but we don’t have an idol; in football we have great players, but we don’t have a great idol.

– Gabriel Medina or Ítalo Ferreira in surfing…

– Medina is one of the greats. We have [gymnast] Rebeca (Andrade), but she’s very young. And football is another story, it’s very controversial. Joao is on his way to becoming an idol, one of Brazil’s great idols, but it’s too much for a 19-year-old who is still 40th in the world and has only won one tournament. A very nice expression I heard the other day was from a woman who said, ‘I have saudade of Orkut.’ Orkut was like a social network, you joined communities. I would say I didn’t like Meligeni and join a community of people who didn’t like Meligeni, or one where he was much loved. And that’s how life was. Today, if you don’t like Meligeni, you want to destroy him. And that happens a lot in politics, it’s happening in religion and a lot in football. And they’re bringing it into tennis. They do it with Bia Haddad.

– The haters…

– The haters kill her when she loses, they tell her she played badly.

– Does Fonseca have haters?

– Of course! Those who say he’s not as good as people say he is.

– So having thick skin is essential in today’s world.

– Yes, that’s why we have to take care of our athletes.

– I’ll come back to the subject: why, if in a handful of months in 1999 and 2000, Kuerten won Roland Garros, reached number one in the world and you reached the semi-finals of Roland Garros, is this the best moment for Brazilian tennis?

– We paved the way for them to take advantage of what Guga mainly did. There were no social networks, there wasn’t as much reach for tennis. We were from a time when if you lost to [Czech tennis player Ctislav] Slava Dosedel, who was ranked 40th or 30th in the world, people would ask you how you could have lost to him. People didn’t know who the world number 30 was, but today everyone knows everything, information is very easily accessible. Of course, Guga and I also took advantage of what Thomaz Koch did, but people still saw tennis as an elite sport. And I understand that in part; a racket is taxed at 70 per cent. I’ve asked for that tax to be removed.

– And did they do it?

– No. Tennis is expensive in Brazil, and it continues to be expensive in Brazil.