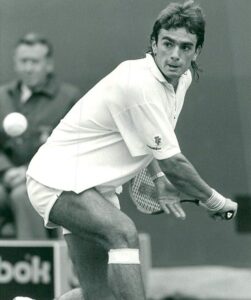

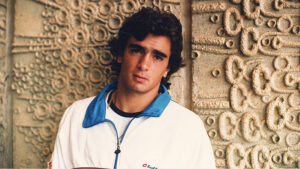

What you see on the courts and in the stadiums is never the whole truth. Let the Argentinian Guillermo Pérez Roldán, whose life at the age of 18 was glory in front of the cameras and an ordeal away from them, say so: capable of taking the then number one Ivan Lendl to the fifth set in the Rome 1988 final, when the matches were over, his father-coach transformed himself: punches in the face, whips on the bed, his head pressed to the point of drowning inside a toilet.

And the fruits of a career, millions and millions of dollars, gone. “I finished my degree and three months later I was poor. I didn’t even have a car. That’s how it was. I called the bank outside, asked for money to go on holiday and there was no more. And there were several million dollars. Besides, we had houses, racehorses, restaurants, flats, and so on. I don’t count on it and I don’t live with it, and I know I’ll never have it.

Pérez Roldán is 52 years old and lives today in Chile, where he works in a club. He has two daughters and a son. Part of the year he also works in Italy, a country he loves. The memory of his game still lingers in Argentina, a country with a passion for tennis that, in the second half of the 80s, was surprised by “the Pérez Roldán”.

Raúl, the father, was the head of a team made up of his children Guillermo and Mariana, Franco Davin and Patricia Tarabini. These were the beginnings of the school in Tandil, a town 300 kilometres from Buenos Aires, which also produced the best Argentine tennis player in decades, Juan Martín del Potro.

If hard, powerful and physical tennis was the trademark of the two Pérez Roldán, the plastic strokes and the magic wrist were the patrimony of Davin and Tarabini.

Davin, a great talent, suffered too many glaring injuries throughout his career, probably affected by a type of training and style of play that not only did not benefit him, but damaged him. It was the style of Raúl Pérez Roldán.

Little was known in the last years of the life of Guillermo Pérez Roldán, who was ranked 13th in the world. In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, with the sport almost completely paralysed, the newspaper “La Nación” published a story in 2020 that shook the whole country. And days ago, the story made an impact in the form of a TV documentary on Star+.

“I tried to commit suicide because I didn’t want to, I didn’t want to anymore”, he confesses in the documentary. He didn’t want to live. He was 18 and had borrowed a gun from his grandfather, the only person he trusted.

“I fired the gun twice and the bullets didn’t come out. In 1988 I just wanted to disappear, I didn’t want to live like this. But the fact that those two bullets didn’t come out meant that I had to go on…”.

Pérez Roldán continued to play and suffer at a level that is hard to imagine. Players such as Martín Jaite, Javier Frana, Franco Davin, Mariano Zabaleta and Mariano Puerta admit in the documentary that Pérez Roldán’s (father) extreme toughness caught their attention. But no one felt empowered to go further, to descend into hell to see if Guillermo could be rescued. Neither did the leaders of Argentine tennis in those years,

“I would have wanted a better father. Let’s see if one day he gives me a hug and I stop being an economic issue”. The phrase paints Guillermo Pérez Roldán in full: behind the image of a tough player, hidden behind that devastating forehand, there was always a tenderness. And his father took advantage of that tenderness, omnipresent in his day-to-day life.

“Losing a match, walking into a room and getting punched in the middle of the mouth with a clenched fist. Or having your head stuck in a bathroom, or being beaten with a belt on top of the bed. Or a robbery of four or five million dollars. Everything I won playing tennis, I didn’t have the next day. My old lady and my old man signed to take the money out of my accounts”.

“I suffered physical abuse. Everybody knew. It was with me. And with my sister at first. But when I started billing myself, my sister took a back seat. I have to say he was a hell of a coach, but a shitty father. It couldn’t be that winning a game was a relief and at certain moments, instead of being able to enjoy myself at 19, I didn’t give any more. I told him: ‘Go on your way, when I need you technically I’ll call you. Buy yourself a field, go to the horses, but leave me alone'”.

Pérez Roldán’s pressure on his children was such that Mariana, who reached 51st in the WTA ranking, won a match at Roland Garros playing her final match with a very serious knee injury. She was never able to play again, tennis was over for her. And part of Guillermo’s retirement had to do with a hand injury he suffered while defending his father during a fight at a gas station in Italy. He never recovered from that, which precipitated his retirement.

“Guillermo had a great forehand, but a heavy physique, his mobility was not good, I would never have thought he would get to what he got to; in that sense, his father did a very good job,” Modesto “Tito” Vázquez, twice captain of the Argentine Davis Cup team, told CLAY.

“Davin and Tarabini were instead two players with exceptional talent. Raúl couldn’t or didn’t know how to take advantage of the virtues they had. At a certain point he took advantage of Franco and Patricia to improve his children. You would see Davin for hours and hours playing against Guillermo from the back court, when his job should have been to attack and play at the net. Raul ended up making them both his sons’ sparring partners”.

And just as Raul moulded Davin and Tarabini’s tennis according to his rigid concepts, Guillermo and Mariana were capable of hurting themselves by following their father: a story of fear and almost blind obedience. A madness.

“My hell is the panic of being beaten, of being outraged, of domestic violence,” recalls Guillermo in the documentary, which is divided into three chapters of half an hour each.

“I had a hard time raising my daughters. I miss them every day and I have to live 14,000 kilometres away. I couldn’t keep my first marriage because I didn’t know how to do things right. But I’m not going to give up, I’m going to start a family”, adds the former tennis player in tears.

The Pérez Roldán’s father, Raúl, appears in the documentary, although it is striking that the former tennis player’s sister, also a victim of his father, does not speak.

When Raúl is asked if he made any mistakes, his answer is shocking: “I was a good coach. That’s for sure. The rest…”.

Guillermo Pérez Roldán’s career ended at the age of 24 after he had won two Roland Garros titles at junior level, won nine ATP tour titles and reached the quarter-finals at Roland Garros.

According to Star+ when promoting the documentary, the former tennis player will travel to Argentina in the next few days to file a criminal complaint against his father.

Days after his first public outburst, Pérez Roldán took the call from the author of this article. He spoke without bitterness, without rancour, with a sometimes candid enthusiasm for what he now feels he is capable of doing. He says tennis needs to teach coaches how to deal with players, he says his story is not the only one, far from it, he says he has a plan, a goal, and that when he speaks again, it will be to tell what he is going to do. And to get it right.

He won’t allow himself to fail: this time, his life is completely his own. Tennis gives him a second chance. And that makes him happy, unbelievably happy.

Until he remembers again and horror covers his face.