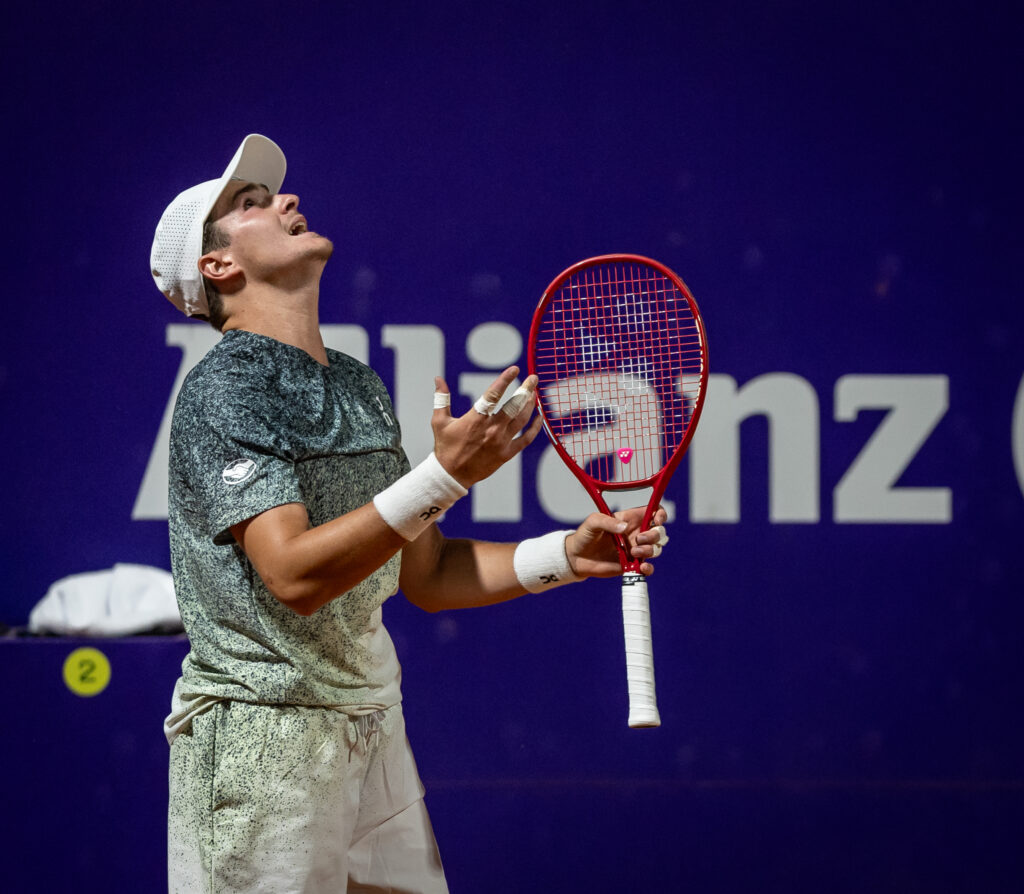

This February is perfectly exposing the two faces of tennis: while the best players in the world compete beneath the skyscrapers of a city in the middle of the desert, in front of a cool and sophisticated crowd that rarely fills the stands, the rackets of the second tier sweat through the South American summer before electric fans who turn any venue into a celebration.

The ATP 500 in Doha, Qatar, has been the stage chosen by Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner for their return this week after the Australian Open. According to La Gazzetta dello Sport, the two best players in the world today received 1.2 million dollars each simply for showing up. As it is not a mandatory event — unlike the Grand Slams or most of the Masters 1000 tournaments — organisers must dig deep into their pockets to attract the biggest stars. And there, Middle Eastern briefcases offer more persuasive arguments than the tournaments on the South American clay swing.

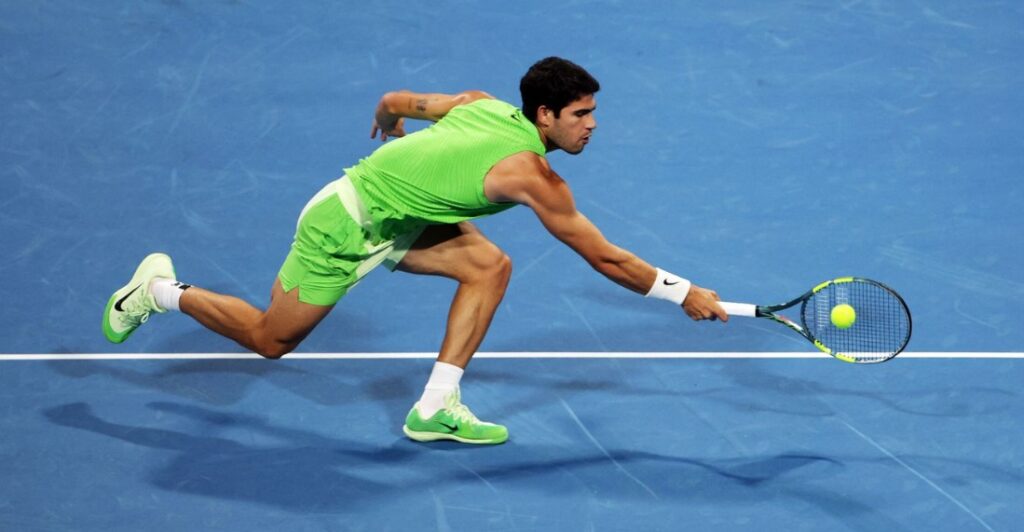

Obviously, that cheque is already a more than compelling reason to understand why Alcaraz replaced the ATP events in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro in his calendar with those in Rotterdam and Doha. But reducing the analysis to a purely financial matter would be a mistake. Which brings us to another number: 150. Because this week in Doha, the world No. 1 celebrated his 150th career victory on hard courts. He, who comes from the country of clay par excellence, who was forged on the orange surface from childhood, understands that hard courts are the present and the future. He knows that if he wants one day to sit at the table of Novak Djokovic, Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer, the path runs through hard courts.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Una publicación compartida por La Arenga del Abuelo (@arengadelabuelo)

Two of the four Grand Slams, six of the nine Masters 1000 tournaments and ten of the 16 ATP 500s are played on hard courts. Add the ATP Finals, and 19 of the 30 most important tournaments in the world take place on the faster surface. Of the remaining 11, eight are on clay and three on grass. Moreover, from 2028, Saudi Arabia will stage a new Masters 1000 in February. It will, of course, be played on hard courts and feature a lucrative prize fund. Another blow to the South American swing, which will have to juggle or reinvent itself to remain on the calendar.

“It’s true that I grew up playing mainly on clay and hardly played on hard courts as a kid,” Alcaraz said in Doha this week, where on Friday he faces Andrey Rublev for a place in the final. “However, if we look at the tour, most of the tournaments — even the biggest ones — are played on hard courts, so I had to adapt and train more on that surface. During the off-seasons, I trained more on hard courts and that helped me gain experience, feel more comfortable and play good tennis.”

“In the end, it’s about adapting. As tennis players, we have to adapt to any situation or surface, and over the years I’ve felt increasingly comfortable on all of them,” added Alcaraz, who already boasts staggering numbers on hard courts despite being only 22.

Hard-court records of leading Spanish players

|

Player |

Record (W–L) |

Total matches |

% win |

|

Carlos Alcaraz |

152-42 |

194 |

78.35% |

|

Rafael Nadal |

518-151 |

669 |

77.43% |

|

Carlos Moyà |

211-141 |

352 |

59.94% |

|

Roberto Bautista Agut |

273-184 |

457 |

59.74% |

|

David Ferrer |

346-199 |

545 |

63.49% |

|

Juan Carlos Ferrero |

178-134 |

312 |

57.05% |

|

Pablo Carreño Busta |

164-130 |

294 |

55.78% |

|

Tommy Robredo |

228-182 |

410 |

55.61% |

|

Fernando Verdasco |

263-237 |

500 |

52.60% |

|

Feliciano López |

277-283 |

560 |

49.46% |