SANTIAGO, CHILE – “How does it feel to break a racquet?” the moderator of the conversation asks Fernando Gonzalez.

“It’s a relief. Now I can say it. And well, also because you didn’t buy them”, says the Chilean, former world number 5.

Gonzalez recalls a time when he was tremendously frustrated. It was the first time he smashed a racquet: “I tried to let off steam and I couldn’t. I was anguished. I was distraught. Until I grabbed the racquet and broke it into Little pieces. It felt like a rebirth. Then I got into this habit, I don’t know if it’s good or bad. From the outside it looks horrible, but for me it was a relief”.

The Chilean didn’t defended the act of destruction of the most precious instrument in tennis. No. It was simply an honest confession during the presentation of the book that chronicles his carrer. Gonzalez chatted in a relaxed tone during the event that celebrated that his legacy is now to be stored in libraries and sold in bookstores.

“Fernando González, the best forehand in history” is the sports biography of the triple Olympic medallist, written by journalist Gonzalo Querol.

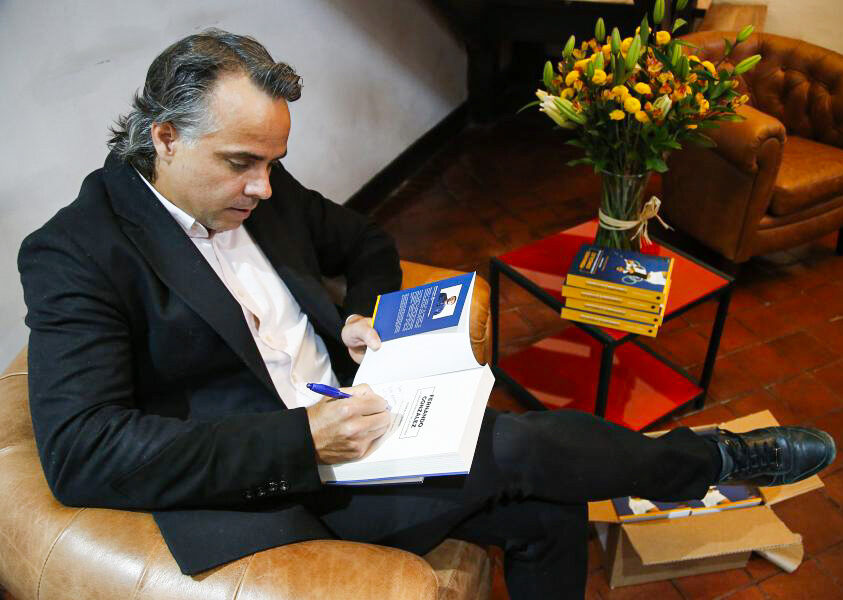

Querol presents it after six years of work, most of that time without yet contacting González, until he had the first draft of the text that delighted the 2007 Australian Open runner-up. “You were acting behind my back,” the tennis player jokes. González then committed himself to the completion of the book.

The author began by reliving the recordings of the matches on Youtube. Then, his first interviewees were the Argentinean stars of the beginning of the millennium. Guillermo Coria, David Nalbandian, José Acasuso and Mariano Zabaleta. “La Legion” knows the Chilean tennis player well, of whom he was a contemporary.

They were followed by about 70 interviewees who nourish with memories, anecdotes and good stories one of the few tennis books that have been published in Chile.

The pandemic helped Querol to progress his work. “Everyone answered during the lockdown. That’s when the book advanced from 40 to 80 percent,” says the man born and raised in La Pincoya, a slum in the northern part of Santiago.

“Many people are ashamed to say that they come from below. The opposite happens to me. I had a beautiful childhood in the suburbs. The only tennis lessons I ever had in my life were there. At that time my dream was to play tennis like González and (Nicolás) Massú.

Querol, a lover of long-term work, studied sports journalism in Buenos Aires: “I fell in love with research. I’m motivated by jobs that require a lot of interviews, data, statistics… anything that requires a lot of preparation. That’s what I love and that’s what the book has”.